Managing Conflict at Work

Conflict at work, organisational conflict, or workplace conflict, is a state of discord caused by the actual or perceived opposition of needs, values and interests between people working together. Conflict takes many forms in organizations. There is the inevitable clash between formal authority and power and those individuals and groups affected. There are disputes over how revenues should be divided, how the work should be done, and how long and hard people should work. There are jurisdictional disagreements among individuals, departments, and between unions and management. There are subtler forms of conflict involving rivalries, jealousies, personality clashes, role definitions, and struggles for power and favour. There is also conflict within individuals – between competing needs and demands – to which individuals respond in different ways.

What is Conflict?

Buelens et al. (2006) define conflict as the “process in which one party perceived that its interests are being opposed or negatively affected by another party”. The word “perceives” in their definition implies that conflict is based on the individual perception of the parties involved and therefore may not necessarily represent reality. Buelens et al. describe conflict as an unfolding process, and as a result, they explain, conflict can be managed.

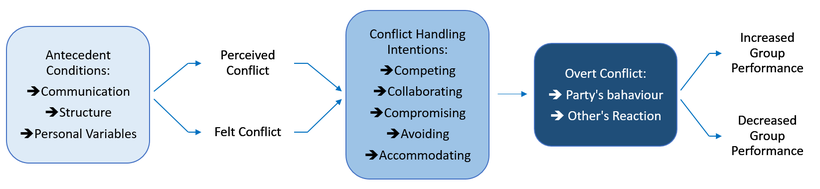

Robbins and Judge (2013, p. 450) explain that the conflict process has five stages:

Stage 1: Antecedent Conditions

While Robbins and Judge (2013) grouped the conditions that create opportunities for conflict to arise into the three general categories communication, structure, and personal variables Buelens et al. (2006, p. 497) identified several factors causing conflict.

- Incompatible personalities or value systems

- Overlapping or unclear job boundaries

- Competition for limited resources

- Inadequate communication

- Interdependent skills

- Organisation complexity

- Unsolved or suppressed conflicts.

- Unmet expectations

- Collective decision making by consensus

- Unreasonable deadlines or extreme time pressures

- Unreasonable or unclear policies, standards or rules

Stage 2: Cognition and Personalisation

Identifying and recognizing the sources of conflict may help managers to take steps in reducing the likelihood of conflict occurring. If any of those factors or conditions negatively affect something one party cares about, then the potential for opposition or incompatibility becomes actualized in the second stage. Two issues may arise in this stage: how the conflict is perceived and how the involved parties feel about it. Looking back to the aforementioned definition of conflict it appears obvious that one or more of the parties must be aware of existing antecedent conditions which, however, does not automatically mean only because a conflict is a perceived that it is personalized. It is on the personal level where conflict is felt, where individuals become emotionally involved, experiencing anxiety, tension, frustration, or hostility. It is emotions that shape perception.

Still, conflict is not always negative and it may be suggested that there is functional and dysfunctional conflict. Functional conflict is usually constructive and allow employees to contribute to a team’s decision-making process in an open and honest manner while still maintaining the acceptance by team members and creating a greater commitment fostering open and honest communications and utilisation of the members’ skills and abilities.

On the other hand dysfunctional conflict usually has its focus is more on personal relationships, is more of a socio-emotional level and therefore its effect on performance is rather negative .

Stage 3: Conflict Handling Intentions

Intentions intervene between people’s perceptions and their emotions and on the other hand their apparent behaviour. Significantly the overt behaviour is influenced by what the parties believe the other party’s intent may be.

Robbins and Judge (2013, pp. 453-454) identified five conflict-handling intentions: competing (assertive and uncooperative), collaborating (assertive and cooperative), avoiding (unassertive and uncooperative), accommodating (unassertive and cooperative), and compromising (midrange on both assertiveness and cooperativeness). Buelens et al. (2006) recognised similar conflict handling styles which are integrating, obliging, dominating, avoiding and compromising.

Competing or Dominating: Obviously here one person seeks to satisfy his or her own interests regardless of the impact on the other parties. While this approach does not accommodate for future co-operations it may be suitable where unpopular decisions have to be made or where the decision is undisputable right or of an ethical nature.

Collaborating or Integrating: The integrating or collaborating style is time consuming as it shows a high concern for one’s own interest while still considering the interests of others involved. This is about putting the emphasis on joint problem solving and collaboratively working on an outcome to satisfy all involved sides by clarifying differences rather than by accommodating various points of view – the typical "win-win" situation.

Avoiding: The avoiding style is where a person recognises an existing conflict and wants to withdraw from or suppress it. While this is suitable for situations where the conflict is trivial or one that is unlikely to be won, however conflict will not be resolved by avoidance.

Accommodating or Obliging: The obliging or accommodating style shows more concern for others’ interest than for the own. Involving self-sacrifice in pursuing the other party’s goal, seeking to appease an opponent may create obligations that can be called upon in the future. This could be suitable in situations where one’s own interest is rather unimportant.

Compromising: In the compromising style there is no clear winner or loser but rather, there is the willingness on both sides to give up something in order to gain something else. This appears appropriate where the opponents are on the same power level while the goals are opposed – the typical “give-and-take” situation.

In addition to Buelens et al.’s (2006) and Robbins and Judge’s (2013) handling styles and handling intentions Appelbaum et al. (1998) propose four more conflict handling strategies:

Smooth: Smoothing over disadvantages that would promote the opposition’s view while gaining acceptance of one’s views by accentuating the benefits.

Maintain: Maintaining the status quo while the action on views that differ from one’s own may be a useful interim strategy allowing to collect more information, to let emotions cool down and/or when more time is needed.

Coexist: The opposing parties jointly determine to follow separate paths for an agreed time period may function as a pilot testing to finally determine which path has greater merit. Suitable when both parties are firm and to assess the effectiveness of each approach after an agreed timeframe.

Decide by rule: Agreeing jointly to use an objective rule such as a vote, lottery, seniority system, or arbitration. Very useful when a decision is required when impartiality is needed.

Apparently intentions or handling styles and strategies are not always fixed but are rather influenced by personality characteristics. They might change in the course of a conflict if the parties are able to see the opponent’s point of view or respond emotionally to the other’s behaviour. Indication is given that people have preferences among the above conflict-handling intentions, strategies or styles (Appelbaum, et al., 1998; Buelens, et al., 2006; Robbins & Judge, 2013) and consequently the opponents may attempt to predict the other’s intentions rather well from a combination of intellectual and personality characteristics based on the perceptions given from past experiences and interactions and therefore may adapt their own strategies and handling styles.

Stage 4: Behaviour

On stage 4 the actual conflict becomes visible which includes statements, actions, and reactions made by the conflicting parties, usually as open attempts to implement their own intentions. Most of us may know that this is a kind of a dynamic process. Even from a minor misunderstanding an increasing spiral of violence could develop when one word leads to another. Robbins and Judge (2013, p. 454) refer to a Conflict-Intensity Continuum along which all conflict exist. It also illustrates the differences between functional and dysfunctional conflict with functional areas on the lower levels and dysfunctional on the highest level.

Annihilatory Conflict

- Overt efforts to destroy the other party

- Aggressive physical attacks

- Threats and ultimatums

- Assertive verbal attacks

- Overt questioning or challenging of others

- Minor disagreements or misunderstandings

No Conflict

For managers it is of great importance to be skilled in conflict management in order to minimise threat levels and maintain conflicts at the functional levels. Knowing the options to de-escalate conflict if it becomes dysfunctional is as useful as knowing how to increase conflict levels when it is too low and therefore unproductive. Robbins and Judge (2013, p. 455) list several conflict-resolution techniques and conflict-stimulation techniques to manage conflict.

|

Conflict-Resolution Techniques |

|

Problem solving Face-to-face meeting of the conflicting parties for the purpose of identifying the problem and resolving it through open discussion. |

|

Superordinate goals Creating a shared goal that cannot be attained without the cooperation of each of the conflicting parties. |

|

Expansion of resources When a conflict is caused by the scarcity of a resource (for example, money, promotion, opportunities, office space), expansion of the resource can create a win-win solution. |

|

Avoidance Withdrawal from or suppression of the conflict. |

|

Smoothing Playing down differences while emphasizing common interests between the conflicting parties. |

|

Compromise Each party to the conflict gives up something of value. |

|

Authoritative command Management uses its formal authority to resolve the conflict and then communicates its desires to the parties involved. |

|

Altering the human variable Using behavioural change techniques such as human relations training to alter attitudes and behaviours that cause conflict. |

|

Altering the structural variables Changing the formal organization structure and the interaction patterns of conflicting parties through job redesign, transfers, creation of coordinating positions, and the like. |

|

Conflict-Stimulation Techniques |

|

Communication Using ambiguous or threatening messages to increase conflict levels. |

|

Bringing in outsiders Adding employees to a group whose backgrounds, values, attitudes, or managerial styles differ from those of present members. |

|

Restructuring the organization Realigning work groups, altering rules and regulations, increasing interdependence, and making similar structural changes to disrupt the status quo. |

|

Appointing a devil’s advocate Designating a critic to purposely argue against the majority positions held by the group. |

Appelbaum et al. (1998, p. 229) propose a four step process for managing conflict and disagreement constructively. Their four steps are: Diagnosis, Planning, Implementation and Follow-up.

Diagnosis: Investigating where disagreements lie in order to be able to handle the situation before it boils over into overt conflict. They see potential sources of conflict in information being interpreted differently, goals that appear to be incompatible, violations of boundaries, unhealed old wounds, and in the fact that symptoms may be confused with underlying causes.

Planning: Choosing one of the aforementioned strategies or a blend of those to develop an action plan along with a backup plan using the mutual agreement of the parties on a time and place to explore differences and a time frame in which to do it. Implement a monitoring process and decide on consequences of failure.

Implementation: Carry out the plan maintaining a tone of mutual respect and goodwill while agreements should be put in writing.

Follow-up: After an agreement has been reached monitor the results to verify that it is being honoured. Reinforcing the behaviour that supports the agreements and in case it was not honoured, it is important to find out why and take corrective action. For the future, learn from experiences with conflict and disagreement.

Stage 5: The Outcomes

As discussed earlier outcomes may be positive or negative, mostly depending on whether the conflict is functional or dysfunctional. Dysfunctionality may arise from too little conflict – apathy, indecision, lack of creativity - or too much conflict – political fighting, reduced group cohesiveness, reduced communication, increased employee turnover. Therefore conflict is only productive and useful within certain parameters. Excessive conflict must be managed appropriately as well as the absence of conflict. Robbins and Judge’s techniques of stimulating and resolving are useful methods to find and manage the individually useful degree of conflict in a team.

In the day-to-day business managers may come across the four main types of situations that may require different negotiation skills and strategies: